You've been asked to develop a new data-driven software application for a library, archive, or museum. Do you focus on the data first, or the user interface?

The answer probably depends on what you're most comfortable with. Software engineers and data scientists are likely to focus on the data and data model. User experience designers and marketers are likely to focus on the interface.

In an ideal world, you would focus on each in turn, or collaborate with people who would focus on the part you're less comfortable with. In the real world, you see many applications that clearly emphasize the data or the interface, often to the detriment of the other.

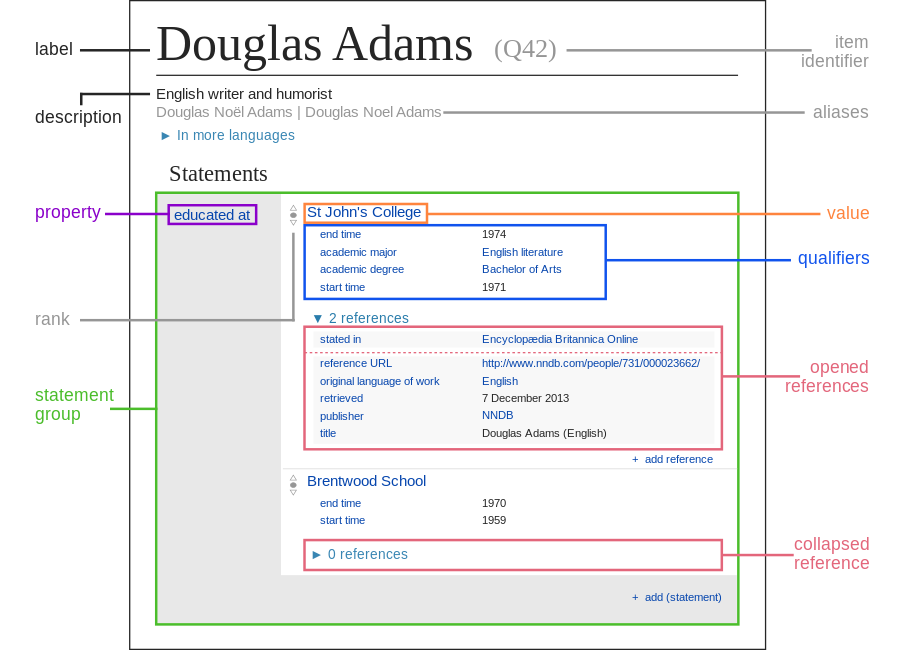

Many projects in the cultural heritage sector are data-first, and prioritize the creation of Linked Data as an end in itself. These projects craft comprehensive data models such as Linked Art or add statements to Wikidata, and are judged by the quality and the quantity of data the project produces. If there's a user interface for the new data it is frequently treated as an afterthought. The interface might be as rudimentary as a SPARQL endpoint or other API. Projects that go one step further might incorporate a web application that displays the data as data: a tangled knowledge graph or tables of RDF statements (as in Wikibase, shown below). Even the best data-first projects rarely provide user interfaces that are more than a thin veneer framing the data model.

Solid is another clear example of a code- and (linked) data-first project. With a few exceptions like Media Kraken, the majority of the apps listed on the Solid apps page are for viewing and manipulating the data in the system as data: pod browsers, RDF editors, etc.

Who is actually using these interfaces? If there are users, they are the project developers themselves, or people with very similar skill sets. For engineers, librarians, and other specialists, developing an application for "people like me" is the path of least resistance. The assumption is that if other kinds of people want to use the system, they can develop their own interfaces by utilizing the carefully-crafted data and APIs. The reality is that very few people have the motivation and capability to develop a new, reusable interface for someone else's data, and the user interfaces a project provides are rarely supplemented.

Many of the practices of product management serve to counter our natural tendency to focus on what we know best -- ourselves, people like us, and the skills and experiences we share. Product discovery processes insist that we get out of our bubbles and talk with different kinds of people in order to find out what matters to them before we start implementing an application.

Those processes naturally lead to focusing on the user interface first. The interface is how users will judge your project. Unless you are developing a system for a technical audience, the vast majority of users don't care about the elegance of your data. You can't make non-technical users care about the underlying data model by putting it front and center. That will only annoy people, and induce them to give up on your system.

In the for-profit world, a user abandoning your application has real consequences, such as lost revenue and damage to a product's and company's reputation. Conversely, many data-first projects emerge from environments where user satisfaction is a second-order concern: academia, cultural heritage institutions, or government agencies.

Software applications for cultural heritage institutions could be the best of both worlds: free to address end user needs in creative ways without being beholden to the narrow concerns of business. The best digital collection interfaces do exactly that: Mitchell Whitelaw's generous interfaces, Olivia Vane's thoughtful visualizations, and others. Those interfaces should be the standard, not the rare exceptions. There is still a place for excellence in data and data models -- not as ends in themselves, but as means of supporting the user experience.